2024-06-28 - Towards a comprehensible OS concept for PCs, inspired by emulators

IndexModern operating systems and their UIs have become excessively incomprehensible over time and even many of the foundational 'metaphors' and 'analogies' they were initially built upon have broken down and no longer hold much relevance to the ways in which they now work, which is both a security problem and a general usability issue.

Emulators (more specifically the kind that emulate old video game consoles) provide an alternate concept for how PC operating systems that is far more intuitive, comprehensible, and inherently presents a smaller surface area for security vulnerabilities.

Loading ROMs

One of the first and most important things users expect from both emulators and PC operating systems is to be able to load up software to run.

For an emulator, loading a ROM is a virtualized analogy of inserting a physical disk or cartridge into the hardware of the game console, which is actually not so different from where PC OSes get their concept for Executable Files, which were originally just a virtualized form of tapes afterall, and that can still be seen in the way the C standard library's basic file I/O functions work.

ROMs of course are Read-Only, just as the name implies, and like the physical CDs and cartridges they are virtualized digital copies of they do not need to be 'installed' before use, nor do they rely on any extra external extra data outside of the ROM, which from a user perspective makes them very simple to understand.

You simply load the ROM (from the emulators UI, by selecting the ROM), and the software runs- that's it. Done.

It is of course _possible_ to develop software for Windows and Linux that exhibit this behavior from a user perspective (eg. the so called 'Portable Apps' for Windows that have been modified for ease of use, running off of USB sticks or CD-ROMs without installation), the problem is that it is also possible to develop software that _does not_.

File I/O as Save Cartridges

In the very early days of game consoles, games stored on ROMs had no way of allowing the player to 'save the game' (although some games would work around this limitation with 'save codes' the player would write down on paper), but it didn't take long for this limitation to be rectified by the introduction of Save Cartridges, or internal writeable save memory within the game cartridge.

In order to emulate Save Cartridges (such as the Sony PlayStation's 'Memory Cards'), emulators typically have an option for the user to virtually insert a Save Cartridge into the virtual console, just as they would insert a physical Save Cartridge into the physical console. As mentioned previously, the original concept of files in PC operating systems is actually not so different from this, but they have diverged in that they now do differ in that while it is the user that inserts virtual Save Cartridges, on modern PC OSes it is the software. Not only can software on modern PC OSes open files for itself, it can also browse the file system for itself too, if there were a physical analogy to this, it would be like a robot freely wandering your house rummaging through your cupboards looks for disks, tapes, cartridges, etc. of it's own volition.

The inversion of authority represented by allowing software to browse and open it's own files without user action (or consent) is not only a security problem, it also makes software far less understandable. An eventual result of this new established norm of software that is given authority over it's own access to files is that it is now commonplace for structure of the software itself to now expand out into multiple files and often even spread itself accross many directories.

On Windows, many programs that could be singular files or ROMs now instead needlessly store data accross a variety of common locations such as:

C:\Program Files\ C:\Program Files (x86)\ C:\ProgramData\ C:\Users\Default\AppData\Local\ C:\Users\Default\AppData\Roaming\

In addition to these, there is more places data is often also stored:

* The executable's directory * Hidden folders and files * The Windows Registry

This scattering of data makes things far more complex and difficult for the average user to undertand when compared to the simplicity of keeping things within a single ROM. Because the data is scattered far and wide, the software also implicitly has to be allowed to browse the filesystem and access many files, and it is allowed to do so silently and invisibly to avoid bothering the user with requests to do so, meaning that the user is mostly completely oblivious to what the software is actually doing. The end result of authority inversion and unnecessary complexity is an unsound security model and a computer system the user is no longer capable of easily understanding- the analogy of files has virtual tapes has fallen apart.

If we re-embrace the idea of a physical analogy for File I/O, one in which the user and only the user has authority to browse and open files (ie. virtual Save Cartridges), then the system becomes comprehensible again and much easier to secure. The key is that the OS UI (like an emulator) must provide the file browser, and it must be invoked by the user choosing to connect a file to the software, not at the software's request.

Windowing and User Input

When you load a ROM on an emulator, the software on the ROM does not create the window, the window is a virtualization of the TV or monitor that the physical game console would have been connected to which it would normally have exclusive use of. Because the software is not responsible for creating it's window, it is unable to behave abusively by creating multiple windows or windows that cannot be closed or minimized, nor can it hide itself by creating no window at all. In much the same way that allowing software to manage it's own files made software more confusing and less secure, and restricting it from doing so achieved the converse, it unsurprisingly turns out that the same is also true for windowing.

When an emulator window is paused or unfocused, the software within the emulator cannot read input from the keyboard and mouse or take screenshots of the host system's desktop environment, everything outside the emulator is invisible to it and it cannot even tell that it has been paused or unfocused. On Windows, there are various APIs software can use to read keyboard and mouse inputs, access the clipboard, take screenshots, and more- all without user action (or consent), and without the window of the program needing to be focused (or even visible, if there even is a window at all).

By following the emulator model, you constrain the software within the realms of what the user likely already expects are it's limitations, greatly improving security and the user's ability to correctly understand the behavior of the system. Taking things like window creation out of the hands of the software also makes things easier for the programmer by greatly simplifying and reducing what their software is expected to handle and provide, allowing for better, simpler, more reliable, smaller programs.

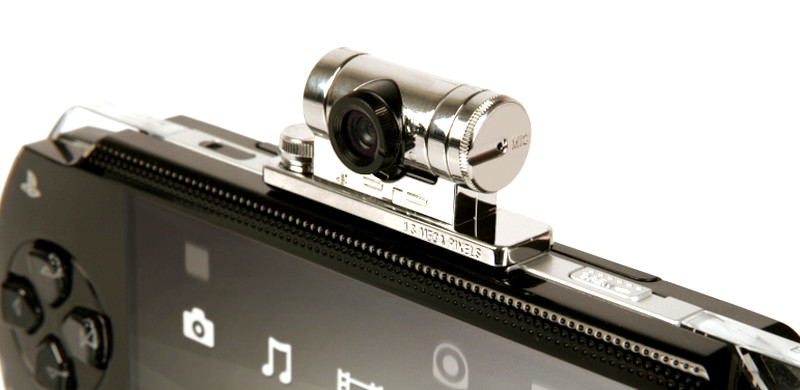

Webcams, Printers and Other Peripherals

Like everything else, peripherals like Webcams, Printers, MIDI devices, and all manner of other accessories are by default of course unavailable to software running within an emulator until they are attached by the intentional action of the user. Placing the authority solely in the hands of the user to plumb the connectivity of peripherals (virtual or physical) to software keeps the behavior of the system understandable and of course makes it much easier to keep things secure as well. Following the Principle of Least Astonishment, nothing unexpected happens when things work this way and the virtualized or emulated objects within a computer system all act as you would expect of their real-world physical counterparts, which is why it turns out to be such a good model for keeping computers comprehensible.

Memory Management

On PC OSes like Windows and Linux, software is allocated memory by the software asking the OS for memory and the OS then almost always then giving the software memory without question, again this happens without the users knowledge or consent and again this is an inversion of authority.

On videogame consoles, nearly all memory is typically allocated to the game (with some memory sometimes reserved for system software), as these systems are only expected to support multitasking to a limited degree, if at all. Emulators of these consoles of course have to emulate this behavior, which usually isn't a problem due to typically running on host hardware with substantially more RAM than the target platform they are emulating. Taking the same approach of allocating all memory to a single program might in some cases be desirable for a PC OS, as computers are much cheaper now and you often only actually want to run one program at a time, but it's not the ideal solution for all circumstances. Replicating the emulator-like behavior of allocating a fixed size allocation of memory to every process regardless of it's needs would of course be quite inefficient as it would give too much memory to some programs and too little to others.

Software marketed for PC OSes such as videogames will typically provide both minimum and recommended system requirements as an advisory to the user. Knowing how much memory is required for software to run at all, and how much is estimated to be necessary for the software to run well, are both useful to the user aid their overall ability to understand the computer system. Allocating the minimum required memory to run a program upon loading, and an optionally larger amount (that may be hinted to the user by recommended system requirements) set by the user, is a good place to start with thinking about how memory management should work on a PC OS, but we can go further. Once a program is loaded and running, it should be possible for the user to voluntarily choose to attach more memory to the program that it might use, similar to the way in which they would attach files (ie. virtual Save Cartridges) or peripherals to a process, so that they may make maximum use of their PC's resources, allocated in the best way they see fit.

A memory management system in which memory is allocated by the user rather than by the processes themselves eliminates the need for swapping to disk and the need for software to use heuristics to guess how much memory to ask for. By putting the user in control of memory it becomes much easier for them to comprehend the behavior of the computer as there will no longer be any unexpected slowdowns caused by memory exhaustion that they must resolve through the Windows Task Manager.

Pause, Savestates, and Memory Hacking

One of the cool things about running software in an emulator, is that much like running software attached to a debugger, you can pause the software, inspect it's internal state, save or restore it's internal state to/from a file or memory, or modify it's memory. These are all capabilities which are very desirable to have when working with software on a PC as well, but are all too often either not available to, or not comprehensible to, the average user. It would be good if by default desktop computing environments would simply provide this basic level of functionality for managing programs.

The typical main function for just about any piece of software written for a desktop computer is some amount of initialization and startup code (such as creating threadpools, allocating memory, creating windows, and registering messages to listen for) followed by entry into an infinite loop processing message events from the OS. Much like with allocating memory, a program typically has to guess at the number of threads it should create based on the number of CPU cores the OS reports the CPU as having, without any explicit knowledge about what other programs might also be running and competing for CPU resources. It should be quite obvious to the user of a PC, how many programs they're intending to run, and which programs they care most that they do not stall or stutter as they compete for potentially limited CPU availability. Given that it is the user and the OS that are aware of the relative priorities and CPU resources available, there really shouldn't be any need for the software to be making thread creation decisions for itself based on guesswork. If it is the OS (at the users request) providing the creation of windows, allocating memory, and creating and scheduling threads, then much of the startup initialization of a typical program can be removed from it's concern. A main function that only serves as an infinite loop to process message events (and yield upon reaching an empty queue) might as well not exists, as the entrypoint could instead simply be a message handling function invoked on each message event, simplifying the program.

Network Connections

Like with everything previously mentioned, emulators, and the emulation of Link Cables, and the way this is handled from a UI perspective, gives us an insight into how PC OSes could do things better by once again removing the authority inversion and going with a simple comprehensible physical analogy controlled by the user.

Put the user in control of IPC and networking, let the user decide when they want a program to be able to communicate with another program either on their PC or over the network. No more confusion from obfuscation, no network connections happening in the background invisible to the user, no unexplained behavior from software failing to make connections it never even informed the user it was making. Provide a simple UI for managing network connections, let the user establish network connections intuitively with their friends using their instant messenger to communicate connection details.

Make networking as simple, easy, and secure, as plugging in a Link Cable.

Pathways to Implementation

Obviously emulators already exist and they run real software, so we know none of this is impossible. Linux, FreeBSD, and Windows, already have much of the required OS-level functionality for sandboxing software and restricting it's capabilities. Compatibility layers allowing software from other operating systems exist for each of these platforms, Wine/Proton runs Windows programs on Linux, FreeBSD can run Linux binaries, Windows has WSL, and so on. Docker runs on both Linux and Windows, so containerized software can be used on either platform.

We don't need an actual emulator just to make PC software more usable, as we're talking about running PC software on a PC, what we need is more akin to Wine/Proton or Docker, we need to sandbox the software, provide a new ABI/API, and most importantly, an appropriate UX for loading, running, and managing programs. What we wish to build is essentially a Desktop Environment, built on the correct set of metaphors, not broken old metaphors that no longer match the reality. The approach we should take to this is a UI-first 'wishful programming' approach, starting with the most important bits, the bits that relate to how the user interacts with the system, and the bits that relate to how the developer programs software for the system, and worry about the nuts and bolts of making changes to the kernel, etc. later.

Compared to developing a high-level emulator for a game console, this should actually be comparatively easier.